Listen to This Article:

When you’re eating at a restaurant, have you ever thought about why the courses come out one after another, rather than all at once? Or why cooks are always saying “Yes, chef,” as if they’re speaking to a commanding officer? Or even about the fact that there are so many professionally trained chefs in the first place?

It wouldn’t be surprising if you said no—these things are so ingrained in food and restaurant culture, it can seem like they’re just “how it is.”

But in truth, these and many other principles are either largely or solely due to the influence of one man—Georges Auguste Escoffier. One of the most influential Western chefs in history, Escoffier introduced many foundational concepts that still define cuisine today, more than a century after he retired from the kitchen.

Let’s take a closer look at the story of our school’s namesake, and learn how he came to leave his lasting legacy.

An Inauspicious Start to a Legendary Career

Georges Auguste Escoffier was born in 1846 in Villeneuve-Loubet, a small village in the French Riviera—a region known for its mild weather, sparkling blue water, and palm-lined beaches, which attracted both wealthy vacationers as well as the premier Impressionist painters of the day. The son of a blacksmith, the young Escoffier initially had artistic aspirations of his own before his father pulled him from school and sent him to work as an apprentice in his uncle’s restaurant in Nice.

Though the thought of being a young apprentice chef on the French Mediterranean coast in the 19th century may sound charming and picturesque, the reality evidently was anything but. Escoffier found himself in an unruly, unsanitary kitchen, full of heavy drinking and outright violence—as was common in restaurants of the age. He was subjected to cruel treatment, particularly on account of his height; he was too short to be able to see over the stoves. (He would eventually start wearing raised platform shoes, a fashion choice he stuck to for the rest of his life.)

The French Riviera, where Auguste Escoffier was born and began his career, was a major winter destination in the latter part of the 19th century.

Despite this inauspicious start, Escoffier resolved to learn the trade and set his sights high; he would later write, “I said to myself, ‘Although I had not originally intended to enter this profession, since I am in it, I will work in such a fashion that I will rise above the ordinary, and I will do my best to raise again the prestige of the chef de cuisine.’”

Rise above the ordinary he did, catching the attention of a Parisian restaurateur who hired him as commis-rôtisseur at the esteemed Le Petit Moulin Rouge in 1865. Escoffier was only 19, but he was already making his way in the culinary world.

As a young man, Auguste Escoffier quickly made a name for himself in the culinary world.

Just months after arriving in Paris, however, he was obliged to enter active military service, postponing his budding career in restaurants. But the interruption didn’t stop his culinary curiosity or ambition—in fact, the experience would have a profound impact on his later career.

A New Perspective That Changed Kitchens for Good

Auguste Escoffier served as an army chef for seven years, including during the Franco-Prussian War between 1870 and 1871. During this time, he observed the efficiency and coordination of military hierarchy; he was impressed by the way large groups could pull off complex activities when everyone had a specific job and knew exactly what to do and whom to report to. This principle stuck in his mind, and was something he would later seek to replicate in his kitchens.

After his service, Escoffier returned to the Riviera, first opening a restaurant of his own in Nice before, in 1884, he relocated a little further up the coast to Monte Carlo to take a new job—working for none other than renowned hotelier Cesár Ritz.

Ritz had already been managing hotels for ten years by this time, earning a reputation for elegance and championing cleanliness and customer service in his establishments. Recognizing Escoffier’s unique talent, he hired him to run his hotels’ kitchens. This marked the beginning of a professional relationship that would last more than 20 years.

Escoffier managed the kitchens in hotels that Ritz managed in both Monte Carlo and Lucerne. During this time, he began to develop and implement many of his new ideas about cuisine. One of his most lasting contributions was the brigade de cuisine—a hierarchical system inspired by his experiences in the military that brought order and efficiency to the kitchen.

Escoffier’s brigade de cuisine introduced a hierarchy that brought order to unruly kitchens.

The brigade de cuisine featured more than 20 different types of chefs and cooks, each responsible for a different specialization—like a poissonnier, who only makes fish dishes, or a patissier, who only makes desserts and pastries. The different positions were arranged in a hierarchy, with certain chefs reporting to others who were responsible for ensuring that everything within their specialized area worked flawlessly. This system of coordinated division of labor was revolutionary, and is still widely practiced throughout the restaurant industry today.

A Tireless Innovator Who Brought Order to Cuisine

Beyond the brigade, Escoffier sought to bring order to cuisine more generally during the time he worked in Ritz’s hotels. Drawing on the work of Antonin Carême, an eminent French chef active in the earlier part of the century who wrote books intended to pass on the principles and techniques of French haute cuisine, Escoffier sought to codify the culinary arts even further. One high-profile example: he built on Carême’s concept of grandes sauces to establish what are now known as the five mother sauces, another foundational concept within Western cooking.

Escoffier sought to codify the culinary arts, so that they could be taught to future chefs.

He also worked to popularize service à la russe—a style of service where individually portioned dishes are brought to diners in a series of courses. This replaced the more traditional service à la française, where multiple courses were brought to the table at once and diners served themselves. While the older style enabled more elaborate presentations, it also meant that the food was often cold by the time you got to try it—if there was any left for you to try at all. Escoffier’s approach meant everyone could try everything, and that the food would arrive at the table hot—novel concepts in French dining at the turn of the century.

Escoffier’s and Ritz’s stars rose together during this time—and attracted attention from as far away as London, where Richard D’Oyly Carte, founder of the Savoy Hotel, recognized their inimitable talents and invited them to take charge of his hotel and its restaurant.

Escoffier culinary renown extended across the European continent, and led to an invitation to manage the kitchen in one of the premier hotels in London.

A Former Apprentice Is Named ‘King of Chefs’

Escoffier and Ritz relocated to London in 1890 to take charge of the Savoy—and, over the next eight years, Escoffier’s culinary inventiveness would go on to transform fine dining in London.

He created many of his iconic dishes during his tenure at the Savoy, such as Filets de Sole Coquelin and Pêche Melba, which he named after the famous opera singer Nellie Melba. With his new, delightful dishes, Escoffier recast the elaborate, exclusive haute cuisine of chefs like Carême as a new cuisine classique—simpler, but no less refined. His food was extremely popular, and the Savoy became one of the premier restaurants in the city.

Escoffier and Ritz left the Savoy in 1898, though their partnership was far from over—they continued to work together, founding eminent hotels in Paris and London. It was during this latter part of his career that Escoffier reportedly earned the title “king of chefs and chef of kings,” bestowed by Kaiser Wilhelm II after Escoffier served him and 146 German dignitaries with an impressive dinner aboard the ocean liner SS Imperator. When congratulating Escoffier on the meal, the Kaiser allegedly told him, “I am the Emperor of Germany, but you are the Emperor of Chefs”—praise which, over the years, transformed into its current rendition.

Escoffier spent decades leading kitchens in some of the world’s finest hotels, such as the Carlton.

A Timeless Gift to Culinarians Everywhere

As if he hadn’t done enough for cuisine already, Escoffier left one more iconic legacy during this stage of his career. In 1903, he published Le Guide Culinaire, a book that enshrined the approach to cuisine that he had developed over his career thus far. The first edition included over five thousand recipes, many of which he created himself starting during his time at the Savoy, and detailed his iconic techniques and innovations.

His objective in creating this book was to leave a resource to train new generations of chefs. Today, more than 120 years later, the book is still in print and is still serving that purpose, standing as a valuable resource for chefs, culinary students, and food enthusiasts around the world.

In 1920, after a career spanning more than 50 years, Escoffier retired from restaurants, though he remained active as a writer, mentor, and industry influencer until his death in 1935.

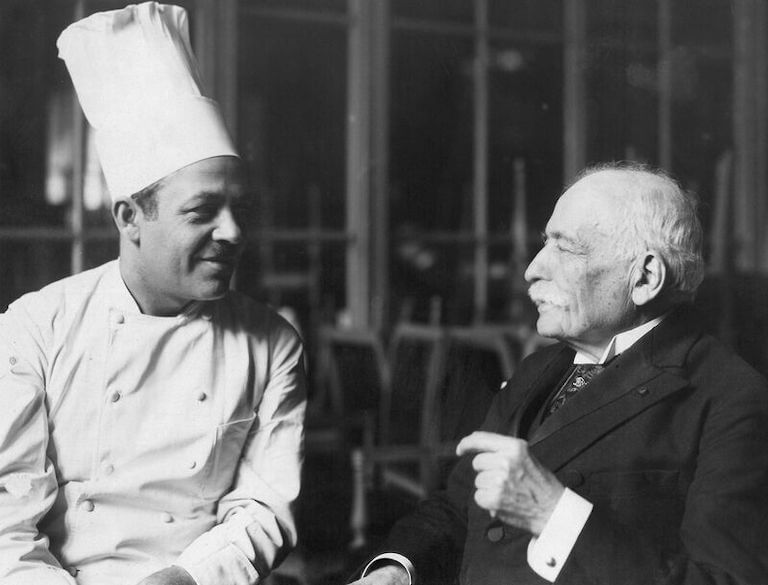

Escoffier remained an active culinary influence until his death in 1935.

In many ways, Le Guide Culinaire encapsulates Escoffier’s commitment to bringing order, simplicity, and clarity to the culinary arts, so that they may be taught to subsequent generations of professional chefs. Michel Escoffier, a member of Auguste Escoffier School of Culinary Arts’ National Advisory Board and Auguste’s great-grandson, has reflected on this aspect of his predecessor’s legacy: “He was very proud of having taught and formed over 2,000 chefs, who in their turn went around the world and promoted French cuisine [and] French techniques.”

Michel Escoffier reflects on his great-grandfather’s legacy, and the pride he would have in Auguste Escoffier School of Culinary Arts’ efforts to continue his legacy of spreading culinary knowledge.

A Lifetime of Teaching Leaves a Legacy of Learning

Through the chefs he directly mentored and those he indirectly influenced through his revolutionary approach to codifying cuisine, Georges Auguste Escoffier proved himself not only a great chef in his own right, but a great educator as well, responsible for professionalizing his trade and ushering in a new era of culinary education and fellowship.

And in the years since his passing, many individuals and organizations have embraced his legacy and joined in his commitment to sharing culinary knowledge.

Nearly a century after his passing, the legacy of Escoffier lives on in culinary organizations around the world.

Among them is Escoffier’s great-grandson, Michel Escoffier. In addition to serving on the Auguste Escoffier School of Culinary Arts’ National Advisory Board, he is also Chairman of the Auguste Escoffier Foundation, an organization dedicated to perpetuating the memory and work of the great chef by organizing culinary training courses, supporting historical and practical culinary research, and maintaining The Escoffier Museum of Culinary Art—located in Villeneuve-Loubet, in the house where Escoffier was born.

His legacy is also carried on by groups like Les Dames d’Escoffier International—an international philanthropic organization dedicated to advocating for women in the food, beverage, and hospitality industries‚—and The Disciples Escoffier International—a group dedicated to honoring Escoffier’s memory, promoting French cuisine, and encouraging young people to pursue culinary careers.

And finally, of course, there is our school—Auguste Escoffier School of Culinary Arts. Founded in the tradition of French culinary schools and drawing on the methods, principles and systems championed by Escoffier throughout his lifetime, our school is committed to helping prepare students for exciting, satisfying careers in the food and hospitality industries.

Escoffier’s Legacy of Learning Is Alive and Well

From untrained newcomer to industry icon, Escoffier left many substantial impacts on world cuisine. But perhaps his most lasting legacy was his commitment to systematizing teaching, so that culinary knowledge could be passed on from one generation to the next.

Escoffier’s astonishing legacy of excellence and learning is alive and well at Auguste Escoffier School of Culinary Arts—where you could have the opportunity to become a part of it. With on-campus and online programs in six distinct areas, Escoffier students can be exposed to a fresh approach to professional culinary training that could help them write the next chapter of their professional careers.

As Auguste Escoffier himself said, “The kitchen will evolve as society evolves, without ceasing to be an art… We must look in ourselves for new ways to leave working methods adapted to the customs and habits of our time.”

IF YOU LIKED THAT ARTICLE, CHECK OUT THESE ONES NEXT:

- How Restaurants Get Michelin Stars: A Brief History of the Michelin Guide

- How to Become a Chef: The Essential Guide

- The Future of Culinary Education Is Here: This Is What It Looks Like

This article was originally published on November 19, 2015, and has since been updated.

*Information may not reflect every student’s experience. Results and outcomes may be based on several factors, such as geographical region or previous experience.